Generative UI and Ephemeral Interfaces

Malleable software. Activision uses AI tools. Dithering explained.

This past week, Google debuted their Gemini 3 AI model to great fanfare and reviews. Specs-wise, it tops the benchmarks. This horserace has seen Google, Anthropic, and OpenAI trade leads each time a new model is released, so I’m not really surprised there. The interesting bit for us designers isn’t the model itself, but the upgraded Gemini app that can create user interfaces on the fly. Say hello to generative UI.

I will admit that I’ve been skeptical of the notion of generative user interfaces. I was imagining an app for work, like a design app, that would rearrange itself depending on the task at hand. In other words, it’s dynamic and contextual. Adobe has tried a proto-version of this with the contextual task bar. Theoretically, it surfaces up the most pertinent three or four actions based on your current task. But I find that it just gets in the way.

When Interfaces Keep Moving

Others have been less skeptical. More than 18 months ago, NN/g published an article speculating about genUI and how it might manifest in the future. They define it as:

A generative UI (genUI) is a user interface that is dynamically generated in real time by artificial intelligence to provide an experience customized to fit the user’s needs and context. So it’s a custom UI for that user at that point in time. Similar to how LLMs answer your question: tailored for you and specific to when that you asked the original question.

Near the end of the short article, they point out some challenges, including usability.

Constantly changing UIs will cause usability problems. Much of users’ understanding of modern web interfaces is rooted in design standards (for example, logos are often in the top left). The more you use a website, the more familiar (and thus efficient) you become. As Gen UI alters the interface based on your needs, you could be shown a different UI every time you use a website. This constant relearning of the interface might cause frustration, especially in the beginning, as users transition from the old ways.

That’s been my concern all along. In fact, consistency is number four in Jakob Nielsen’s Usability Heuristics.

In the same genUI article, Kate Moran and Sarah Gibbons share a speculative example of a user booking a flight. The system knows that the user “never takes red-eye flights, so those are collapsed and placed at the very bottom of the list.” And that she prioritizes cost and travel time so those datapoints are displayed more prominently and the results are sorted accordingly. Can you imagine the support nightmare for UI that’s always changing? How would a support person even begin to troubleshoot?

But let’s get back to this week and Gemini.

Highlighted Links

Geoffrey Litt - The Future of Malleable Software

Geoffrey Litt is a design engineer at Notion. He is one of the authors at Ink & Switch of “Malleable software,” which I linked to back in July. I think it’s pretty fitting that he popped up at Notion, with the CEO Ivan Zhao likening the app to LEGO bricks.

In a recent interview with Rid on Dive Club, Litt explains the concept further:

So, when I say malleable software, I do not mean only disposable software. The main thing I think about with malleable software is actually much closer to … designing my interior space in my house. Let’s say when I come home I don’t want everything to be rearranged, right? I want it to be the way it was. And if I want to move the furniture or put things on the wall, I want to have the right to do that. And so I think of it much more as kind of crafting an environment over time that’s actually more stable and predictable, not only for myself, but also for my team. Having shared environments that we all work in together that are predictable is also really important, right? Ironically, actually, in some ways, I think sometimes malleable software results in more stable software because I have more control.

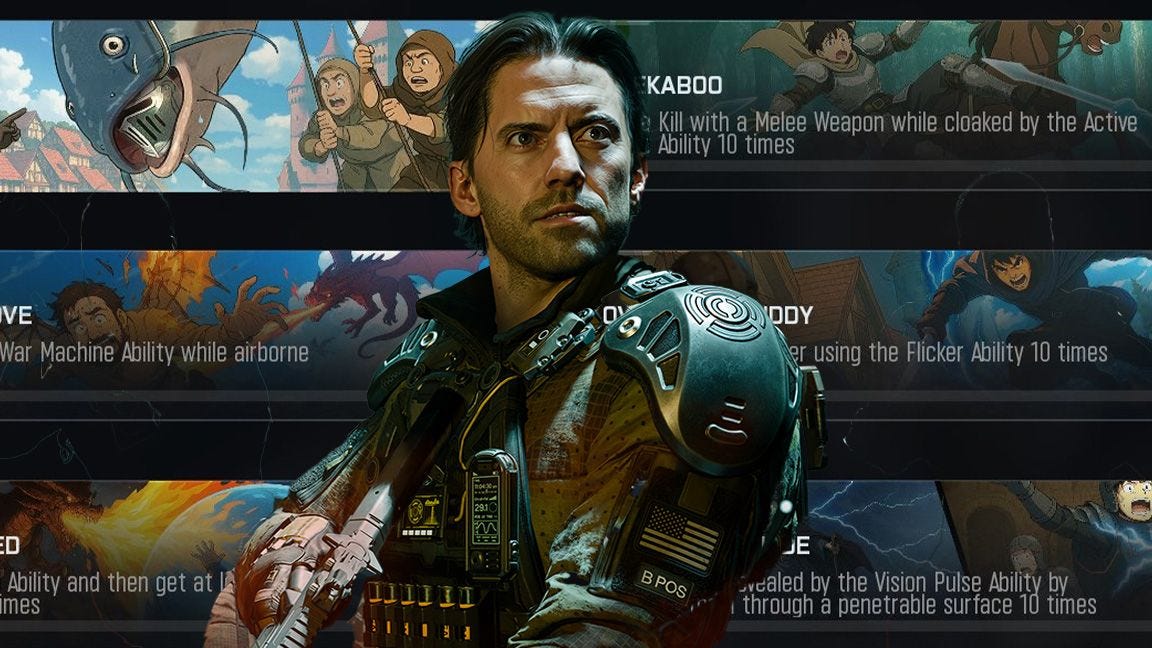

Why Call of Duty: Black Ops 7’s AI art controversy means we all lose

I wouldn’t call myself a gamer, but I do enjoy good games from time to time, when I have the time. A couple of years ago, I made my way through Hades and had a blast.

But I do know that the publishing of a triple-A title like Call of Duty: Black Ops takes an enormous effort, tons of human-hours, and loads of cash. It’s also obvious to me that AI has been entering into entertainment workflows, just like it has in design workflows.

Ian Dean, writing for Creative Bloq explores this controversy with Activision using generative AI to create artwork for the latest release in the Call of Duty franchise. Players called the company out for being opaque about using AI tools, but more importantly, because they spotted telltale artifacts.

Many of the game’s calling cards display the kind of visual tics that seasoned artists can spot at a glance: fingers that don’t quite add up, characters whose faces drift slightly off-model, and backgrounds that feel too synthetic to belong to a studio known for its polish.

These aren’t high-profile cinematic assets, but they’re the small slices of style and personality players earn through gameplay. And that’s precisely why the discovery has landed so hard; it feels a little sneaky, a bit underhanded.

“Sneaky” and “underhanded” are odd adjectives, no? I suppose gamers are feeling like they’ve been lied to because Activition used AI?

Dean again:

While no major studio will admit it publicly, Black Ops 7 is now a case study in how not to introduce AI into a beloved franchise. Artists across the industry are already discussing how easily ‘supportive tools’ can cross the line into fully generated content, and how difficult it becomes to convince players that craft still matters when the results look rushed or uncanny.

My, possibly controversial, view is that the technology itself isn’t the villain here; poor implementation is, a lack of transparency is, and fundamentally, a lack of creative use is.

I think the last phrase is the key. It’s the loss of quality and lack of creative use.

I’ve been playing around more with AI-generated images and video, ever since Figma acquired Weavy. I’ve been testing out Weavy and have done a lot of experimenting with ComfyUI in recent weeks. The quality of output from these tools is getting better every month.

With more and more AI being embedded into our art and design tools, the purity that some fans want is going to be hard to sustain. I think the train has left the station.

Dithering (Part 1)

Someone on X recently claimed they “popularized” dithering in modern design—a bold claim for a technique that’s been around since Robert Floyd and Louis Steinberg formalized it in 1976 and Bill Atkinson refined it for the original Macintosh. The design community swiftly reminded them that revival isn’t invention, and that dithering’s current moment owes more to retro-tech aesthetics meeting modern GPU pipelines than to any single designer’s genius.

Speaking of which, here’s a visual explainer by Damar Aji Pramudita that’s worth your time on how dithering actually works. Apparently it’s only part one of three.

What I’m Consuming

AI’s Dial-Up Era. Hype and heavy infrastructure spend define an early, dial‑up‑style phase of AI. Outcomes will differ by industry, hinging on how much unmet demand gets unlocked versus how fast automation boosts productivity. Radiology and historical cases in textiles, steel, and autos show a pattern: employment rises when cheaper, abundant services expand demand, then falls once demand saturates while automation keeps improving. Job categories—especially in software—will reshape, with more people doing engineering‑type work without the title. Even if many ventures fail, today’s exuberant investments will leave durable infrastructure that powers the next wave. (Nowfal / Wreflection)

Jeff Tweedy - “How to Write One Song.” Jeff Tweedy’s onstage conversation with Song Exploder’s Hrishikesh Hirway at Solid Sound 2024 explores his book How to Write One Song, extending its practical creative insights beyond songwriting to life and personal growth. (Hrishikesh Hirway / Song Exploder)

How to Write a Joke. Elliot Kalan introduces a structured “joke farming” system for generating jokes on demand, drawing from the underlying logic and parts of jokes rather than waiting for inspiration. (Roman Mars / 99% Invisible)

Wow, the part about genUI being 'dynamically generated in real time' trully stood out to me. It's mind-bending to think about! Thanks for this super insightful look at such an important design future.

The furniture analogy for maleable software really resonates with me. I think Litt's point about stability through control is key - we don't want interfaces that rearrange themselves, we want the ability to arrange them ourselves and have that stick. The paradox is that giving users more control actully creates more consistency, not less.