TRON and How Users Forgot to Be Programmers

Explaining color space, redefining human in the loop, and where's my pizza?

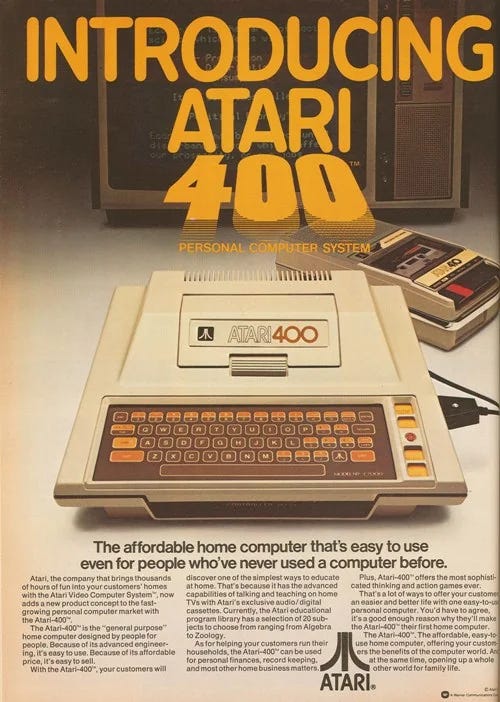

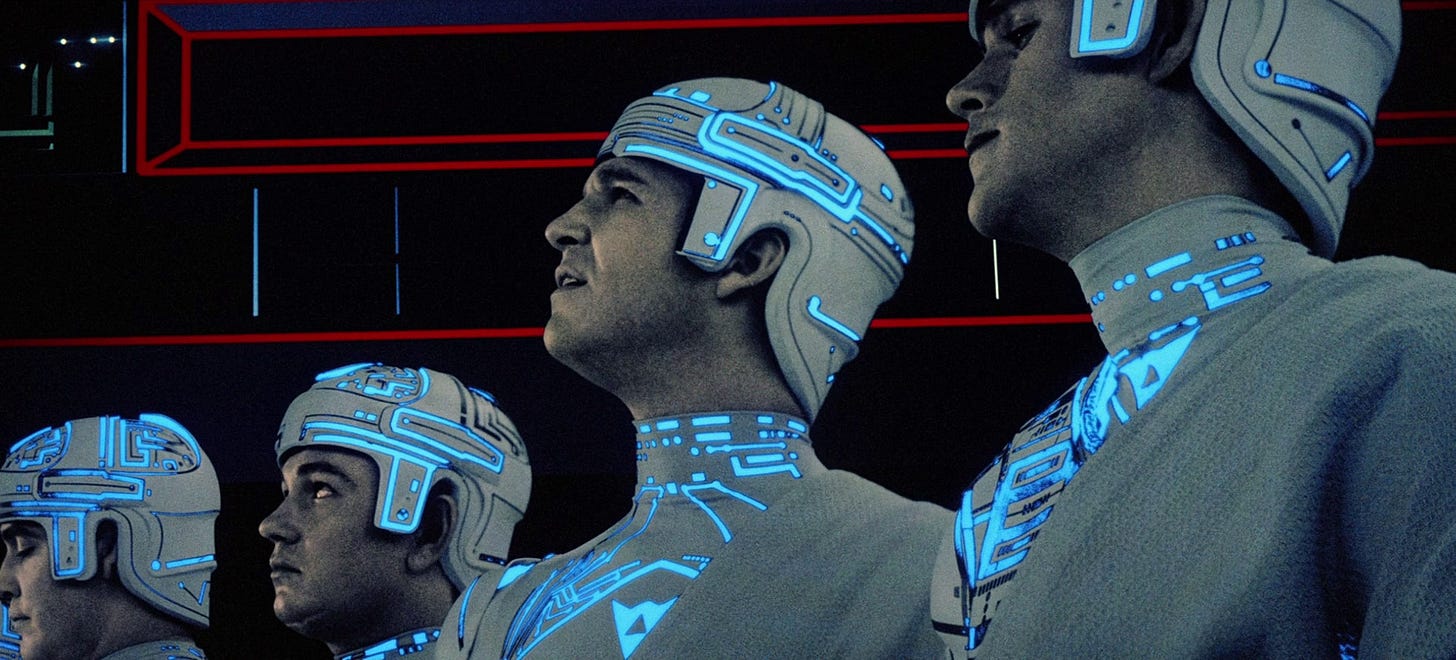

I rewatched the 1982 film TRON for the umpteenth time the other night with my wife. I have always credited this movie as the spark that got me interested in computers. Mind you, I was nine years old when this film came out. I was so excited after watching the movie that I got my father to buy us a home computer—the mighty Atari 400 (note sarcasm). I remember an educational game that came on cassette called “States & Capitals” that taught me, well, the states and their capitals. It also introduced me to BASIC, and after watching TRON, I wanted to write programs!

Back in the early days of computing—the 1960s and ’70s—there was no distinction between users and programmers. Computer users wrote programs to do stuff for them. Hence the close relationship between the two that’s depicted in TRON. The programs in the digital world resembled their creators because they were extensions of them. Tron, the security program that Bruce Boxleitner’s character Alan Bradley wrote, looks like its creator. Clu looked like Kevin Flynn, played by Jeff Bridges. Early in the film, a compound interest program who was captured by the MCP’s goons says to a cellmate, “if I don’t have a User, then who wrote me?”

I was listening to a recent interview with Ivan Zhao, CEO and cofounder of Notion, in which he said he and his cofounder were “inspired by the early computing pioneers who in the ’60s and ’70s thought that computing should be more LEGO-like rather than like hard plastic.” Meaning computing should be malleable and configurable. He goes on to say, “That generation of thinkers and pioneers thought about computing kind of like reading and writing.” As in accessible and fundamental so all users can be programmers too.

The 1980s ushered in the personal computer era with the Apple IIe, Commodore 64, TRS-80, (maybe even the Atari 400 and 800), and then the Macintosh, etc. Programs were beginning to be mass-produced and consumed by users, not programmed by them. To be sure, this move made computers much more approachable. But it also meant that users lost a bit of control. They had to wait for Microsoft to add a feature into Word that they wanted.

Of course, we’re coming back to a full circle moment. In 2025, with AI-enabled vibecoding, users are able to spin up little custom apps that do pretty much anything they want them to do. It’s easy, but not trivial. The only interface is the chatbox, so your control is only as good as your prompts and the model’s understanding. And things can go awry pretty quickly if you’re not careful.

What we’re missing is something accessible, but controllable. Something with enough power to allow users to build a lot, but not so much that it requires high technical proficiency to produce something good. In 1987, Apple released HyperCard and shipped it for free with every new Mac. HyperCard, as fans declared at the time, was “programming for the rest of us.”

Highlighted Links

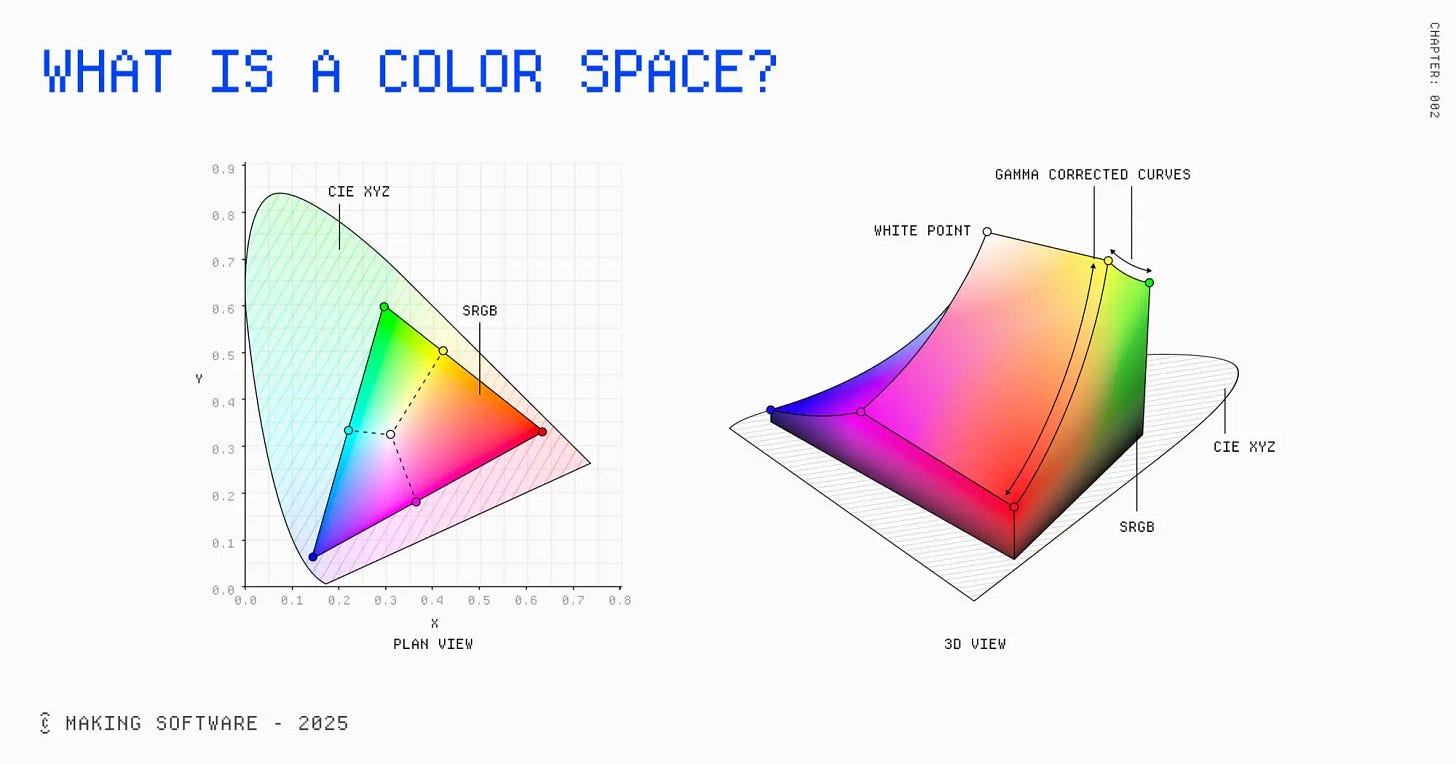

Making Software: What is a color space?

I have always wanted to read 6,200 words about color! Sorry, that’s a lie. But I did skim it and really admired the very pretty illustrations. Dan Hollick is a saint for writing and illustrating this chapter in his living book called Making Software, a reference manual for designers and programmers that make digital products.

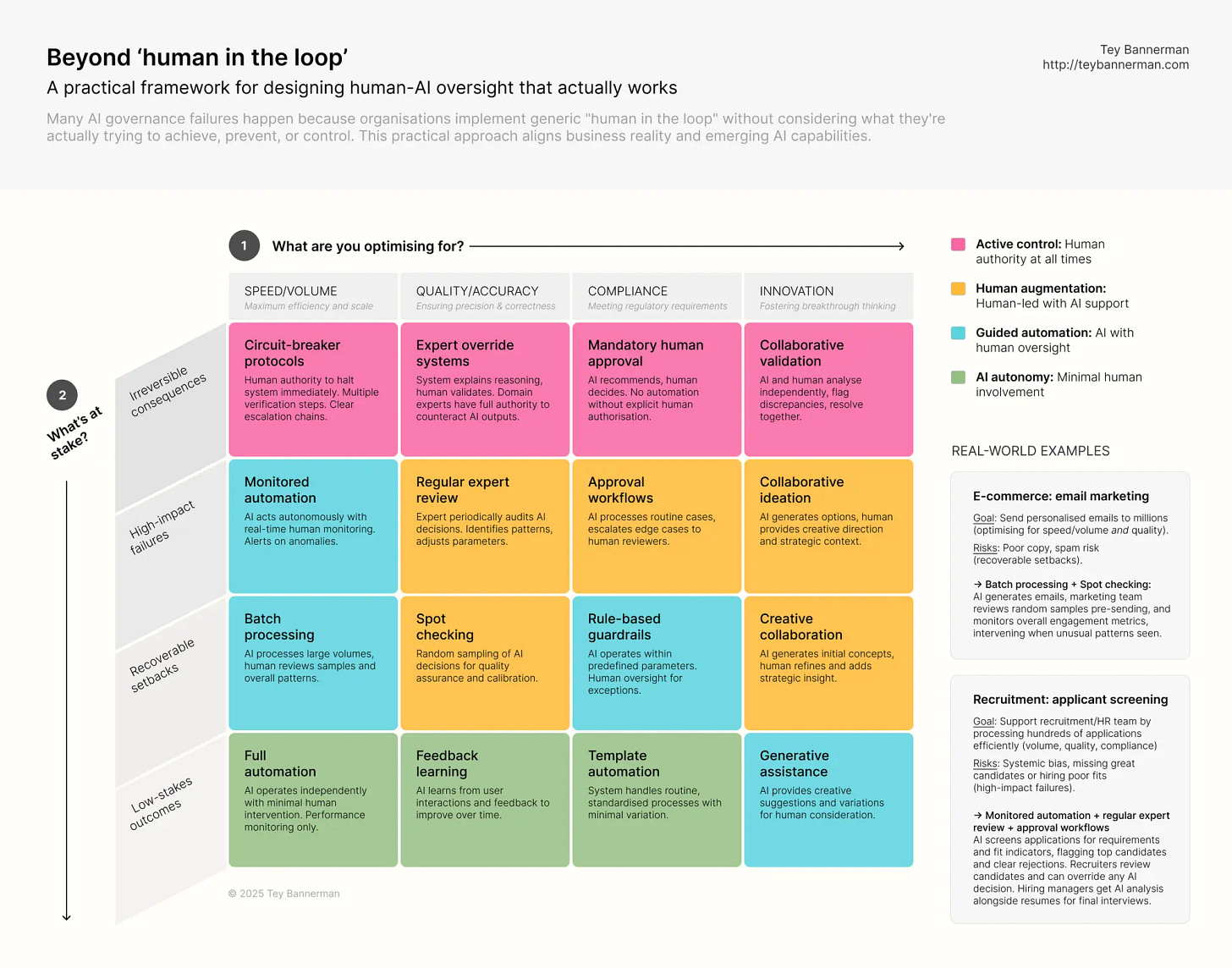

Redefining ‘human in the loop’

Designer Tey Bannerman writes that when he hears “human in the loop,” he’s reminded of a story about Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, a Soviet Union duty watch officer who monitored for incoming missile strikes from the US.

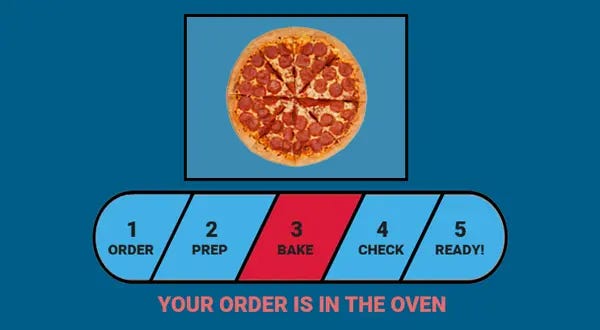

How the Domino’s pizza tracker conquered the business world

Hard to believe the Domino’s pizza tracker debuted in 2008! Alex Mayyasi weaves together a tale of business transparency, UI, and content design, tracing—or tracking?—the tracker’s impact on business since then. “The pizza tracker is essentially a progress bar.” But progress bars do so much for the user experience, most of which is setting proper expectations.

What I’m Consuming

There’s logic behind your gut feeling. Charles Peirce explained that “abduction” is the logic behind gut feelings—it’s making the best guess to start thinking and learning. This way of reasoning helps designers and AI users ask better questions and explore ideas, not just look for quick answers. To think well, we must embrace doubt, test guesses, and be willing to change our minds. (Nate Sowder / UX Collective)

The rewards of ruin. The collapse of empires, often dramatized as catastrophic, was generally less traumatic for ordinary people than elite-written history suggests; in fact, the fall of oppressive states frequently led to improved health, more equality, and better conditions for the majority. Rather than descent into chaos, such periods typically brought social benefits for the 99%, indicating that the narrative of inevitable disaster after empire collapse is a myth shaped by the perspective of the ruling 1%. (Luke Kemp / Aeon Magazine)

The Math Trick Hidden in Your Credit Card Number. The Luhn algorithm is a simple math test that checks if a credit card number is typed correctly. It catches common mistakes like wrong digits or swapped numbers without needing to contact the bank. This saves time and money by quickly spotting errors before deeper checks are done. (Jack Murtagh / Scientific American)