Architects and Monsters: Designers Knew What They Were Building

Plus: The power of critique, a UX designer's reading list, and continued discourse on the junior hiring crisis.

According to recently unsealed court documents, Meta discontinued its internal studies on Facebook’s impact after discovering direct evidence that its platforms were detrimental to users’ mental health. In a 2020 research project code-named “Project Mercury,” Meta scientists found that people who stopped using Facebook for a week reported lower feelings of depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Rather than publishing those findings or pursuing additional research, Meta called off further work and internally declared that the negative study findings were tainted by the “existing media narrative” around the company.

This isn’t surprising. But it is damning.

As more evidence comes to light about Meta’s failings—and possibly criminal behavior—we as tech workers, and specifically designers making technology that billions of people use, have to do better. My previous essay was an indictment on the algorithm. But I’ve come across a couple of pieces recently that bring the responsibility closer to UX’s doorstep.

We know about infinite scroll. We know about doomscrolling. We know the attention economy generates billions in ad revenue by selling us to advertisers. But what really stings is this observation from Elvis Hsiao:

Those designers knew what they were building. Internal documents, whistleblower testimony, and the simple existence of features like screen time limits prove the companies understand the addictive nature of their products, but prioritize profits over well-being.

So what can we as designers and makers of technology do?

Perfectly timed with the release of Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, Elenor Howe uses Victor Frankenstein as a parabolic tale—arguing that we’ve acted with the same hubris, building systems optimized for profit and engagement, then hiding behind diffused responsibility when systemic harms emerge. She proposes something she calls “The Architect’s Mandate”—a Hippocratic Oath for tech.

In the full essay, I break down her seven mandates and make the case for why we should cosign them. We’ve wrought a monster, but we can’t abdicate our duties any longer. We have to make things better by making better things.

Highlighted Links

Critique

Critiques are the lifeblood of design. Anyone who went to design school has participated in and has been the focus of a crit. It’s “the intentional application of adversarial thought to something that isn’t finished yet,” as Fabricio Teixeira and Caio Braga, the editors of DOC put it.

A lot of solo designers—whether they’re a design team of one or if they’re a freelancer—don’t have the luxury of critiques. In my view, they’re handicapped. There are workarounds, of course. Such as critiques with cross-functional peers, but it’s not the same. I had one designer on my team—who used to be a design team of one in her previous company—come up to me and say she’s learned more in a month than a year at her former job.

Further down, Teixeira and Braga say:

In the age of AI, the human critique session becomes even more important. LLMs can generate ideas in 5 seconds, but stress-testing them with contextual knowledge, taste, and vision, is something that you should be better at. As AI accelerates the production of “technically correct” and “aesthetically optimized” work, relying on just AI creates the risks of mediocrity. AI is trained to be predictable; crits are all about friction: political, organizational, or strategic.

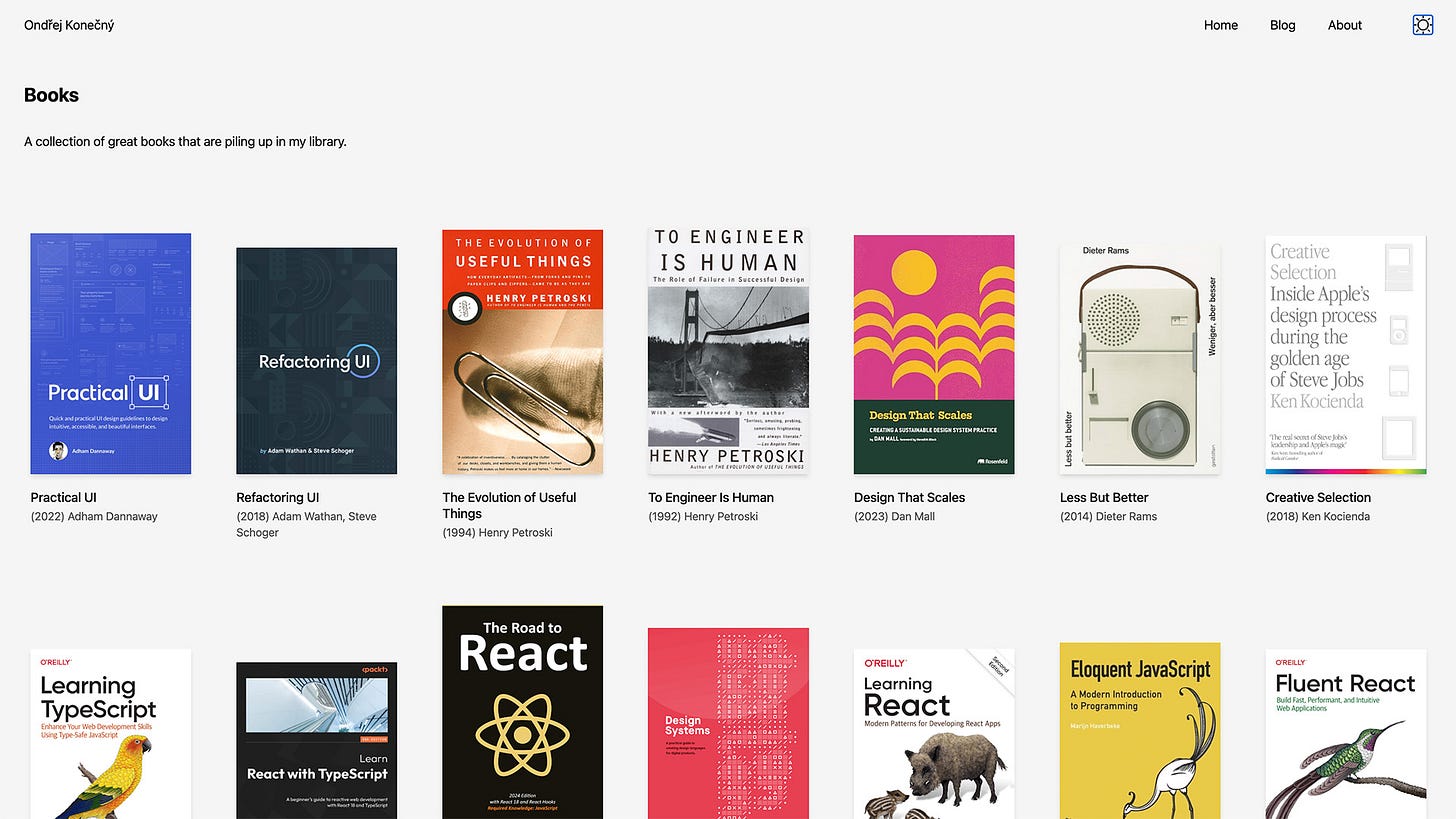

Ondřej Konečný | Books

Designer and front-end dev Ondřej Konečný has a lovely presentation of his book collection.

My favorites that I’ve read include:

Creative Selection by Ken Kocienda (my review)

Grid Systems in Graphic Design by Josef Müller-Brockmann

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

Don’t Make Me Think by Steve Krug

Responsive Web Design by Ethan Marcotte

The Junior Hiring Crisis

As regular readers will know, the design talent crisis is a subject I’m very passionate about. Of course, this talent crisis is really about how companies who are opting for AI instead of junior-level humans, are robbing themselves of a human expertise to control the AI agents of the future, and neglecting a generation of talented and enthusiastic young people.

Also obviously, this goes beyond the design discipline. Annie Hedgpeth, writing for the People Work blog, says that “AI is replacing the training ground not replacing expertise.”

We used to have a training ground for junior engineers, but now AI is increasingly automating away that work. Both studies I referenced above cited the same thing - AI is getting good at automating junior work while only augmenting senior work. So the evidence doesn’t show that AI is going to replace everyone; it’s just removing the apprenticeship ladder.

And then she echoes my worry:

So what happens in 10-20 years when the current senior engineers retire? Where do the next batch of seniors come from? The ones who can architect complex systems and make good judgment calls when faced with uncertain situations? Those are skills that are developed through years of work that starts simple and grows in complexity, through human mentorship.

We’re setting ourselves up for a timing mismatch, at best. We’re eliminating junior jobs in hopes that AI will get good enough in the next 10-20 years to handle even complex, human judgment calls. And if we’re wrong about that, then we have far fewer people in the pipeline of senior engineers to solve those problems.

What I’m Consuming

Is Gen X Actually the Greatest Generation? (Gift link) Disclosure, I’m Gen X, hence my obsession. Gen X’s formative years of independence, DIY culture, and ironic anti‑authoritarianism produced enduring art across music, film, TV, and magazines, now experiencing renewed appreciation. Shaped by latchkey childhoods, less parental oversight, and pre‑internet focus, the cohort’s works—spanning hip‑hop’s golden age, Black New Wave cinema, and feminist voices—privileged authenticity over market dictates and found community among peers. Ongoing debates about generational boundaries aside, the ethos—skeptical of conformity yet politically engaged—remains a compelling counterpoint to today’s hyper-mediated culture. (Amanda Fortini / The New York Times)

Are Claude and Gemini Winning the AI Race? Plus, How We’re Using the Latest Models | EP 167. For me, the most interesting segment of this episode of Hard Fork is where Kevin Roose and Casey Newton discuss their new favorite models: Google’s Gemini 3 and Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5. Gemini 3 is praised as a fast, reliable workhorse that meaningfully boosts day‑to‑day tasks—fact‑checking quickly, organizing timelines, sequencing sources, and pulling passages from long documents—even if it lacks much personality. Claude Opus 4.5 feels “special” to use: empathetic without flattery, consistently in the same “musical key,” and unusually strong at deep research and textual style transfer, producing prose that can convincingly mirror a writer’s voice. They see Gemini’s advantage in sheer speed and Google’s distribution, while Opus stands out for humane, aligned behavior and enterprise‑first incentives that avoid engagement‑driven quirks. Together, those traits make Gemini and Opus their two daily drivers for different strengths. (Hard Fork / The New York Times)